Discovering The Sidhe - Are There Fairy Folk?

Maybe this is a chapter that is more suited for the wonderful heritage of fairy storyteller Eddie Lenihan and fairy whisperer Pat Noone. But here, instead, I will share my experiences and interpretations from stories I have heard throughout my life.

‘Sidhe’, or earlier ‘Sí’ spelling, do not seem to be words that have been tampered with over the centuries.

I am saying this because folklore went through quite a re-interpretation during the 19th century. That was due to there being a boom in printing press sales due to their lower prices, better cost and easier availability of wood pulp for making paper, plus a lot more of the population had learned to read and write. The result of all of that would have been more people to write content for the people with printing presses, and more people able to read what was produced by printing presses.

During the early days of scribing, especially during the middle Medieval years, I am sure something similar happened, but much slower. There was the challenge of transcribing the oral ‘telling’ into the limited vocabularies of the scribes. During the 19th century, I am sure there were a lot of oral stories transcribed into print too, but the oral stories being a lot more understandable then.

As there were few to no investigative journalists and reporters, during the early 19th century, it was these old tales and rhymes that were printed and sold in the street by the ‘broadsheet’ sellers.

The buyers of these would have invited friends to join them in house drawing rooms, or around cottage fires, to exchange their shared interpretations and re-enactments of what was written and printed.

I feel traditions were altered rapidly back then. I am sure they would have been translated and printed into forms most popular with the people. The motivation of printers was obviously to produce what would sell the easiest, rather than be concerned about accuracy and authenticity.

Not much different today. When a film/movie screenplay interprets from a book it becomes very different to the book, because the film companies want to sell their films and attract the most people to them. The films produced being a mix of film distributor’s profit motives mixed with their director’s egos.

From the new printing industry and wider education in reading and writing, the old folklore transformed into a new ‘Celtic Romanticism’ culture.

If I was living back then I do not think I could blame this happening. Suddenly nature and old ways were being ripped up and disconnected from a large population of people during the fast establishing Industrial Revolution. With that fast culture change shock, I am sure people wanted to retreat back to the ways that were, but still take advantage of some modern comforts that the Industrial Revolution brought to many people, rather than return back to the old cruelty.

I believe it is from these ‘Celtic Romanticism’ re-enactments that causes many of us who may say ‘Sidhe’ today to also imagine images of ‘fairy folk’. I must admit that sometimes I do get into that myself.

Part of my own reason, I think, is that during this current rapid moving age of the internet, leading into social media, this has also accelerated our re-interpretations of folklore too. Re-interpretation has been at a much more rapid rate during these past 20 years than the Celtic Romance ‘revolution’ through the 19th century, and the sharing of ‘broadsheets’ then.

But let us try to re-imagine an interpretation of the ‘Sidhe’ before there was any mass printing, but place ourselves during the times when there was hand scribing. I am especially thinking of the Medieval age from the 5th century to 15th century. I know, it’s hard to let go of our modern thoughts to place our minds and imagination into that ancient position.

What I personally imagine is the oral tellers describing the ‘Sidhe’ to the scribes, and the scribes relating that as being descriptions of ‘mounds’. I am sure some scribes reacted with some puzzled “so what?” responses.

It seems that ancient languages were not focused on ‘things’ like our current languages do, but on conditions of what was going on. Maybe describing a condition from actions?

When these oral tellers were talking about a ‘mound’ to a scribe, their language was probably really describing, or introducing, what was going on in that mound.

Many people, probably most people now, are familiar with the mythology and stories of the Tuatha De Danann, people that some folks nickname ‘The Fairy Race’, and have done so for some time.

It seems for a long time storytellers have described the Tuatha De Danann as being half human, and half fairy race. Also the Tuatha De Danann are told of as being a race who made a pact with a tribe of invading Milesians.

To attempt to keep this quite complex story simple, the pact was that the Milesians would rule above ground, while the Tuatha De Danann would rule the underground, underworld, ‘otherworld’.

It appears that he Tuatha De Danann got the rough side of this ‘pact’. It is told that they entered the underground world through mounds that are now passionately called, ‘the fairy hills of Ireland’, with names such as Knockninny,

Knocknarea,

and Knocknashee.

What I have just said there is an incredibly simple description of a very profound story. Fragments of extensions of that story I dip into as I move through the Nature Folklore of other seasons on the year.

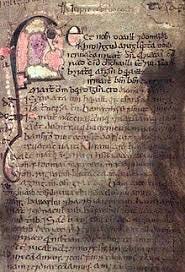

The Lebor Gabála Érenn translations, that were first scribed around the 11th century, are the main archive source of the stories of the arrivals of the Tuatha De Dannan, Formorians, and Milesians on this island that has become Ireland.

Modern scholars question whether there was actually a Milesians tribe. Or was this a story told to simplify telling stories of a bunch of tribes arriving. Stories were simplified for easier storytelling. Much like the line of thinking of Mary, Joseph, and Jesus being a simplified trim downed version of a large family, or even small tribe of people with shamanic like heritage.

I do not think we will ever know what that actual story of the ‘Milesians’ is, or what inspired their existence, was.

I believe that during the 19th century, during reprints of the the Lebor Gabála, the title of that collection was extended to Leabhar Gabhála Éireann or Leabhar Gabhála na hÉireann.

To me, the Lebor Gabála, is a wonderful collection of poems and stories compiled into some sort of order just like the Old Testament of the Bible. Like the Bible, the Lebor Gabála has been through several translations. Each translation changed some meaning, perhaps according to the agendas of the patrons of the translations? … but I am drifting.

The stories, within this collection, continue to describe that after the Tuatha De Danann were underground the Milesians discovered that they could not farm as well as the De Danann people did, as it seems that the Milesians were forest people, more than being farmers. Somehow, it seems that the forests of Ireland at the time were not sustaining them, though some storytellers speculate a climate change issue was going on then too.

Some stories I have heard, in the past, have told that part of the balanced deal with the underworld Tuatha De Dannan was for them to fertilise the seeds underground and roots of crops there too, to ensure good yield above ground when the sun warms the plants. It seems to be that from those underworld fertility legends that the stories of the Sidhe, the fae world, and the fairies have evolved, and have been told for at least 3000 years.

Among these underworld Sidhe beings we are told of, within the Lebor Gabála Érennare, are the Aos sí, or Aes sídhe, who live underground within the Sidhe mounds.

Within the the Lebor Gabála Érenn there is also reference to the daoine sídhe, doine sìth, who are said to be spirits of our ancestors that are said to have returned to earth to be the spirits, or sprytes, of nature that are connected and loyal to the queen goddess.

That reads and sounds like a spirit’s beehive, doesn’t it? And like the ‘beehive', the stories inspired by The Lebor Gabála Érenn talk of a kind of parallel world on earth. Where these spirits emerge from the Sidhe mounds, buzz, buzz, and mingle among us. To do some pollinating maybe?

And to make the stories more interesting, they tell of Sidhe mischief and trickery deeds. Sadly this can head off into excessive fear mongering storytelling, I feel. And that’s not good as I feel that could cause people to become fearful of nature itself.

One example of this, that I interpret, has been encouraging people that it is safer and more spiritual to worship within stone built and enclosed churches than to gather together out in the woods or beside water. I suppose being within human built constructions is safer, when there are predators around.

Earlier, I mentioned the Aos Sidhe, living in the ‘mounds’ that are told of as being beautiful entity beings of the Sidhe realm. But they are also told as being very fierce and very temperamental guardians of fairy forts. They are also described as being defenders of nature’s own Hawthorn Trees, Chieftain Trees, ‘the Nobles Of The Wood, and natural springs that we have dressed up as Holy Wells.

Perhaps the best known stories of retaliations by the Aos Sidhe are the Stolen Child deeds, stories about the ‘changelings’. These are stories of healthy boy babies being swapped with unhealthy babies during the middle of the night.

This story was made quite famous by W.B. Yeats through his poem ‘The Stolen Child’ .

During my next Chapter article in this ‘Discovering Sidhe’ series, I will talk more about the ‘Stolen Childs’ and also the ‘Banshees’, and other folklore described deeds of the Sidhe.

Meanwhile, here is Claire Roche performing, ‘The Stolen Child’ by W.B. Yeats along with the poem script …

Do you write, or would like to write and publish? Do you write about nature, water, woodlands, animals and ancient folklore etc. You could write on this Substack platform and also connect what you publish to ‘Nature Folklore’ and our audience, plus be featured on our 'Nature Echoes' weekly live show. Use the button below to create your own independent Substack channel and message me for suggestions and help too …

I love that poem! 💕 I had never considered that those different names for the Sidhe might be different groups of people living within the Otherworld, I had just assumed they were different references, perhaps from different communities or storytellers, for the Tuatha de Danann.

Wow! Ali, what you wrote there is almost a complete personal substack of your own. Lovely. I’m under pressure to get another job done this evening, so will come back to this when calmer. From a flash read you seem to have put into your own words most of what I have been saying, and take that as a bit of a compliment plus good writing from yourself.

Yes, as I understand it, ‘Sidhe’ was probably first a description of the mounds, and then imagination and visions put all of these other stories into the mounds. Even these days if I am by these mounds or coming down children sometimes ask “tell me a story about the dragons up there, mister”. Part of that is due to me always wearing my ‘Nature Folklore’ t-shirts as i have barely got any other tops in my wardrobe.